Introduction

The brotherhood of Freemasons is not

identical with the brotherhood of humankind. Humanity includes everyone, but

Freemasonry excludes all persons who are not of mature age, sound intellect and

good character.

Most Grand Lodges have additional exclusionary requirements

regarding:

(a) gender: Grand Lodges for men only; for women only; but some for men and

women (liberal Grand Lodges)

(b) religious belief: Grand Lodges for monotheists; for Christians only; but

some for any religion or none (adogmatic Grand Lodges)

And some Grand Lodges exclude persons because of their:

(c)

race or colour of skin.

The large group of Grand Lodges which

are only for men who believe in the Great Architect of the Universe, and which

are generally in amity with each other, does not have an official name, but is

sometimes called ‘mainstream’. Sadly, some mainstream Grand Lodges

believe race, or colour of skin, to be a valid criterion for admission or

rejection.

Historical background of Black Freemasonry in the USA

North

American Freemasonry today has a serious problem in coming to terms with a

legacy from the eighteenth-century importation of sub-Saharan Africans as

slaves. Some ‘free’ Africans became Freemasons and obtained a warrant from

England for African Lodge of Boston, under the Mastership of Prince Hall.

African Lodge was granted a charter by the Grand Lodge of

England (Moderns) in 1784, which arrived in Boston in 1787. Prince Hall

immediately sent to England a report[1]

containing the lodge by-laws, a list of officers and members of the lodge,

including Fellow Crafts and Entered Apprentices, and a promise to send a

donation to the Grand Charity at the earliest opportunity. The lodge was not

admitted to the fellowship of the other lodges in and around Boston, and it

developed in isolation. This was the beginning of racial segregation among

Masons in North America.

Prince Hall's first 'Annual Return' to the Grand Lodge of England, 1787.

Prince Hall continued as Master of the lodge until his death

in 1807. From 1797 to 1826, he and his successors chartered a number of lodges

in Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and New York, while remaining—as far as they

knew—subordinate to the Grand Lodge of England.[2]

In fact, the two rival Grand Lodges in England (the Antients and the

Moderns) had united in 1813, and omitted all US lodges from their

combined roll of lodges. In 1827 African Lodge of Boston declared its

independence and became African Grand Lodge.[3]

Over the next 20 years the segregated Freemasonry which had

sprung from African Lodge continued to grow, but was beset by disputes between

lodges and Grand Lodges, of which there were several by this time. In their

isolation, they attempted to resolve early quarrels and schisms by forming a

National Grand Lodge, superior to their State Grand Lodges, but this has

resulted in two rival groups of Masons, each claiming descent from the original

lodge chartered from England: the State Grand Lodges of ‘Prince Hall

Affiliation’ (PHA) and the National Grand Lodge and its subordinate Grand Lodges

of ‘Prince Hall Origin’ (PHO).

Today, the Grand Lodges of

Prince Hall Affiliation (PHA) are numerically much stronger than the National

Grand Lodge and its subordinate state Grand Lodges of Prince Hall Origin (PHO),

and PHA has spread far beyond the bounds of North America.

|

|

Grand Lodges |

Members (estimate) |

? where |

|

PHA |

47 |

180,000 |

worldwide |

|

PHO |

24 |

20,000 |

USA |

fig 1

Of the 47 PHA Grand Lodges, two are in Canada, two in the

Caribbean, and one in Africa. Many of the PHA Grand Lodges also have lodges in

the US military, stationed all over the world.

Among the mainstream Grand Lodges in the United States, generally those in the

north found technical arguments why Freemasonry in the Black population was

‘unlawful’, whereas those in the south simply wrote into their constitutions,

regulations or other documents that no ‘Negro’ was fit to be made a Mason, and

re-enforced it with a prohibition in the Obligation of their own candidates. On

several occasions between 1860 and 1960, individual Grand Lodges made statements

favourable to the descendants of African Lodge of Boston, with regard to their

‘regularity’, but on each occasion were forced to recant by the withdrawal of

‘recognition’ by other US mainstream Grand Lodges. Several overseas Grand Lodges

extended recognition to individual Black Grand Lodges, but with no permanent

beneficial results. It proved a slip!

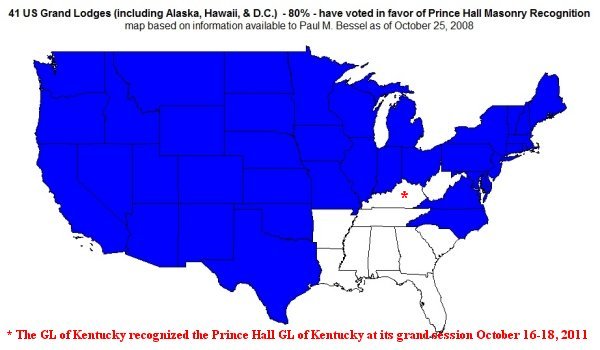

After 1960, several northern US Grand Lodges approached the questions of

regularity and recognition more cautiously and with more determination. From

1989 onwards, recognition has proceeded piecemeal between Black and White Grand

Lodges in the US, followed by recognition by some Grand Lodges outside the US.

However, 20 years later, all PHO Masons and nearly half of all PHA Masons remain

unrecognised by any Grand Lodge, for reasons which will be examined shortly.

It has proved a slip, also!

Recommended reading

Inside Prince Hall

(2003), by David L Gray, gives an accurate account of the history of Prince Hall

Freemasonry from the PHA point of view.

Out of the shadows (2006), by

Alton G Roundtree (PHA) and Paul M Bessel (mainstream), meticulously documents

the recognition process between mainstream and PHA Grand Lodges, and contains an

accurate account of the history of the National Grand Lodge. Many of the

authors’ findings favourable to PHO regularity of descent from African Lodge

have been contested by PHA researchers, but none has been disproved. Alton

Roundtree has another book at the printers, which documents PHO history in

greater detail.

The many books by the late Joseph A

Walkes Jr (PHA) provide more detail about the Prince Hall Fraternity.

For an

outsider’s point of view, see my own research papers on Bruno Gazzo’s excellent

‘Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry’ website at

: ‘Our

segregated brethren, Prince Hall Freemasons’ (1994), and ‘Prince Hall revisited’

(2004).

‘Bogus’ Black Grand Lodges

In addition to the mainstream, PHA and

PHO Grand Lodges in the United States, there are close on 200 other groups

claiming to be Masonic. Most of them have been located by members of the

Phylaxis Society, an organisation which began as a PHA equivalent of the

Philalethes Society, but which has added other functions, including

investigation and ‘outing’ of these other groups.

In addition to the mainstream, PHA and

PHO Grand Lodges in the United States, there are close on 200 other groups

claiming to be Masonic. Most of them have been located by members of the

Phylaxis Society, an organisation which began as a PHA equivalent of the

Philalethes Society, but which has added other functions, including

investigation and ‘outing’ of these other groups.

Coordination of this task is the responsibility of the Society’s ‘Commission on

Bogus Masonic Practices’, which:

- compiles information on ‘bogus’ Grand Lodges

-

publishes the information in the Phylaxis

magazine and on the Phylaxis website[4]

-

joins internet discussion groups and educates

members of ‘bogus’ organisations regarding the difference between them and PHA

Masonry.

I am indebted to the Commission for

much of the information about these ‘bogus’ groups, but note with regret that it

also targets PHO Masons for ‘re-education’.

Clues to the origins of Black Masonic Grand Lodges can often

be gained from what they call themselves. With one exception (Liberia), PHA

Grand Lodges are ‘Free & Accepted Masons’, F&AM. Grand Lodges under the National

Grand Lodge (PHO) are ‘Free & Accepted Ancient York Masons’, FAAYM. Other Black

Grand Lodges, the ones deemed ‘bogus’, are usually ‘Ancient Free and Accepted

Masons’, AF&AM. These differences are sometimes referred to as 3-letter,

4-letter and 5-letter Masons. Another indication of ‘outsider’ status is its

affiliation with a ‘Grand Congress of Grand Lodges’ or a ‘Supreme Council’, or

styling itself a ‘Scottish Rite Grand Lodge’.

Many Grand Lodges in the ‘bogus’ category trace their history

to a renegade PHA or PHO individual or lodge, either directly, or via a further

breakaway. Some are (or claim to have been) chartered by a body outside the

United States, while some are openly self-starters, and some are rogues and

charlatans.

Among degree-peddling self-started groups are: the International Free & Accepted

Modern Masons and Eastern Stars, which pays a bonus to recruiters, runs an

insurance scheme and offers reduced rates to ministers of religion; the

International Masonic Association and Eastern Star, which touts a Masonic

endowment scheme for men, women and children, and has ‘paid leaders’; and

a Knights Templar Organization which sells ‘awards’ by mail.

Timothy Drew, the self-proclaimed Prophet Drew Ali, founded a

religion based on the belief that African Americans were descended from Moors

and were of Muslim heritage, and in 1913 he established the Moorish Science

Temple. His teachings included financial advice and social security measures,

and he compiled a book entitled The Holy Koran of the Moorish Science Temple

of America, sometimes called the ‘Circle 7 Koran’. Its message was a mixture

of Christianity and Islam, with a dash of Freemasonry. From this came the Clock

of Destiny Order Moorish Masonic Jurisdiction, known as ‘Clock Moors’ and other

pseudo-Masonic bodies such as Kaaba Grand Lodge.

Timothy Drew, the self-proclaimed Prophet Drew Ali, founded a

religion based on the belief that African Americans were descended from Moors

and were of Muslim heritage, and in 1913 he established the Moorish Science

Temple. His teachings included financial advice and social security measures,

and he compiled a book entitled The Holy Koran of the Moorish Science Temple

of America, sometimes called the ‘Circle 7 Koran’. Its message was a mixture

of Christianity and Islam, with a dash of Freemasonry. From this came the Clock

of Destiny Order Moorish Masonic Jurisdiction, known as ‘Clock Moors’ and other

pseudo-Masonic bodies such as Kaaba Grand Lodge.

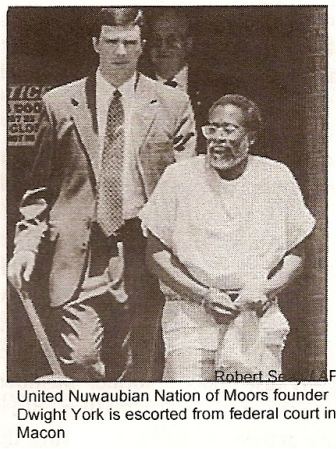

In 2002, under the heading ‘Masonry gone mad’ a special

edition of the Phylaxis magazine featured the rise and fall of a poseur

with many names and faces, who claimed to be from another planet, and

established himself as Grand Master of the Supreme Grand Lodge of Nuwaubian

World Wide Masonic Lodges. This was part of a larger scam that included the

establishment of a ‘Nation’ in rural Georgia, where thousands of followers lived

and waited to be transported from earth by a passing comet. The end came

with the arrest of their leader and his subsequent trial and sentence of

imprisonment for 135 years for kidnapping, child sexual abuse and other crimes.

Problems and solutions

Today, approximately half the

Freemasons and half the Grand Lodges in the world are in North America—in

Canada, USA and Mexico. The problems under consideration relate to USA and to a

lesser extent to Canada, where there are about 250,000 men of African origin in

Grand Lodges which are not within

the mainstream group of Grand Lodges. Most members of Canadian and US mainstream

Grand Lodges are of European origin, although membership of some of these Grand

Lodges is multi-racial, with a few members of Latin-American, Asian, Pacific,

and even African origin. The main problem is how to bring these other Masons of

African origin into the fellowship of mainstream Freemasonry. In theory, the

choice lies between:

(a) amalgamation of Grand Lodges in the same geographic area; and

(b) recognition as equal, independent bodies.

In practice, amalgamation is not an

option because the smaller group would perceive itself as losing its identity

and proud history.

Recognition has its own problems. To understand these, it is

first necessary to remind ourselves that the terms ‘regularity’ and

‘recognition’ are not interchangeable.

Recognition is a question of

fact: either Grand Lodge A and Grand Lodge B recognise each other, or they do

not. If they recognise each other, then their members may visit each others’

lodges and Grand Lodges, and possibly even become members of each others’

lodges. But recognition must be consensual. A unilateral recognition, where

Grand Lodge A ‘recognises’ Grand Lodge B, but B does not ‘recognise’ A, brings

no benefits or privileges.

Within the confines of a particular Grand Lodge,

regularity is also a question of fact; a member of the Grand Lodge is

regular because he was made a Mason under circumstances prescribed by that Grand

Lodge in a lodge chartered by that Grand Lodge. The Grand Lodge considers its

members, its lodges, and itself to be regular. But outside the confines of that

Grand Lodge, the question of regularity is only an opinion. For example, Grand

Lodges A, B, and C all consider themselves to be regular. Grand Lodges A and B

agree that each other is regular, but may differ over whether Grand Lodge C is

regular. Regularity, then, is in the eye of the beholder.

Regularity is a prerequisite for recognition. Each Grand

Lodge has its own criteria for recognition. Most mainstream Grand Lodges have

very similar, but not necessarily identical, criteria. Many adopt the list

originating from the United Grand Lodge of England, sometimes with local

variations. In general terms that list may be summarised as:

- regularity of origin,

- regularity of conduct,

- autonomy, and

-territoriality.

Interpretation of those terms would

seem to vary somewhat.

As we have seen, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Massachusetts

began with a single lodge chartered by England in 1784, which declared its

independence in 1827 and thus became a one-lodge Grand Lodge, voluntarily placed

itself under the authority of a National Grand Lodge in 1847, dividing its one

lodge into three, then declared its independence from the National Grand Lodge

in 1873. Nevertheless, in 1994, England was prepared to accept that as being

‘regularity of origin’ at the time it occurred.[5]

It can be argued from that finding that the National Grand Lodge was also

regular in origin.

It has long been accepted that a Grand Lodge must be

autonomous and not be under, or share authority with, another body such as a

Supreme Council, but it would appear that an exception is made for St John

(Craft) Grand Lodges under the Scandinavian 10-degree system.

There are many exceptions to the US ‘exclusive territorial

jurisdiction’ principle and, as we have seen in Greece in recent years, the

English version of consensual shared territory may be backed up by what could be

interpreted as coercion.

The other side of the coin

Prince Hall Masons have been

segregated from their mainstream counterparts for over two hundred years, on the

basis of their African origin and the colour of their skin. All that time they

have maintained their regularity of conduct, and hoped for acknowledgment that

they are true Masons. It has become clear to them that, while recognition has

slowly been accorded in the north and the west over the past 20 years, there is

virtually no hope of recognition in the ‘deep south’. Not surprisingly, some of

them look towards the other Black Grand Lodges which do not have a clear claim

of origin back to African Lodge of Boston, and feel that they should be working

towards unity with their ‘brothers OF the skin’ rather than recognition by US

mainstream Masons as ‘brothers UNDER the skin’. But those with a clearer

understanding of Freemasonry see that this is not just a North American issue,

but one which concerns, or should concern, worldwide Freemasonry.

The majority of those seeking recognition look no further

than the mainstream Grand Lodge in their own state, and perhaps to the ‘home’

Grand Lodges of England, Ireland and Scotland. Most do not permit dual or plural

membership, and few understand the concept of having an official representative

at another Grand Lodge. Perhaps more importantly, they have no history of

visiting lodges outside their own jurisdiction, and it does not seem to occur to

them that, for true equality in Freemasonry, they should be able to visit lodges

throughout the world. Consequently, many do not seek further recognition in

North America or overseas, and seem reluctant to respond to overtures from other

mainstream Grand Lodges. There are a few exceptions, of which the prime example

is the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Connecticut, which has exchanged recognition

with more than 30 mainstream Grand Lodges.

Of the ten PHA Grand Lodges which have not obtained recognition within their own

state, only one has had the vision and courage to seek recognition widely

overseas. In 2002, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia wrote to 50 Grand

Lodges worldwide, seeking recognition. It had few replies, but three of the six

Grand Lodges in Australia responded favourably. The Grand Lodge of Tasmania, the

Grand Lodge of South Australia and the Northern Territory, and the United Grand

Lodge of Victoria have all exchanged recognition with the Prince Hall Grand

Lodge of Georgia, despite the fact that it does not have recognition from the

mainstream Grand Lodge of Georgia or the United Grand Lodge of England—with no

adverse effects. The result is that in the American state of Georgia these

Australian Grand Lodges recognise two Grand Lodges in the same geographic

location that do not recognise each other.

The Grand Lodge of New Zealand and all six Grand Lodges in Australia have also

taken ‘affirmative action’. All PHA Masons may visit Australian and New Zealand

lodges, if they produce proof of current membership of a PHA lodge and pass the

usual tests for visitors, even if their Grand Lodge has not formally exchanged

recognition. This has been widely publicised, and no mainstream Grand Lodge has

complained.

South Australia has gone two steps further. It has indicated that it is prepared

to extend the practice of recognising more than one Grand Lodge in the same

area, beyond the confines of North America, by exchanging recognition with both

the Grand Orient of Italy and the Regular Grand Lodge of Italy. And South

Australia no longer follows English practice in visiting lodges in other

recognised jurisdictions; if a South Australian Mason visits a lodge in a

jurisdiction recognised by South Australia, and finds another visitor lawfully

present, whose Grand Lodge is not recognised by South Australia, the South

Australian is not obliged to leave

the lodge or to avoid association with that other visitor. This acceptance of

the judgment of the host lodge is sometimes called the ‘when in Rome’ rule.[6]

The point is that these variations on usual practice have not caused an uproar

in mainstream Masonry, and they are worth consideration by other jurisdictions

in seeking to assist in solving the problem in North America. Let us examine the

problem and possible solutions in some detail.

PHA and mainstream

PHA Grand Lodges fall into one of two

categories:

(a) those with in-State or in-Province recognition (33 Grand Lodges with

about half of all PHA Masons); and

(b) those without such recognition (11 Grand Lodges with about half of all

PHA Masons).

To obtain their full inheritance as

mainstream Masons, group (a) should be encouraged to seek wider recognition,

both in North America and elsewhere.

Of those in group (b), ten Grand Lodges are in USA, in the ‘deep south’ where

slavery was still lawful at the start of the civil war in 1861. These have

little hope of achieving in-State recognition in the near future, and other US

mainstream Grand Lodges are unlikely to recognise them without it, but

mainstream Grand Lodges outside North America can extend recognition—and have

begun to do so. This gives them an opportunity to gain part of their

inheritance.

The other Grand Lodge in group (b) is the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Alberta,

formed in 1997. There is a persistent rumour that it has faded away and no

longer meets, but a reliable Canadian source disputes that claim, and the matter

needs further investigation.

PHO and mainstream

The National Grand Lodge (NGL) is not

recognised by any mainstream Grand Lodge. It would be very difficult for the NGL

to obtain recognition from US mainstream Grand Lodges which are based on State

boundaries and are suspicious of any national movement in US Freemasonry. Under

current mainstream practice, a single exchange of recognition would require the

consent of all PHA and mainstream Grand Lodges in the 27 states where there is

an NGL presence—54 opportunities to veto the proposal. Furthermore, at least

eight of those 27 mainstream Grand Lodges have refused to recognise their PHA

counterparts, and would certainly reject the NGL.

Recently the NGL has been corresponding with the United Grand Lodge of England,

seeking recognition. The response indicates that England would not recognise the

NGL without American consent. But recognition of the NGL by mainstream Grand

Lodges outside the US avoids this problem if those mainstream Grand Lodges are

prepared to follow the precedent of the Australian Grand Lodges with Georgia.

If PHO Grand Lodges erected by the National Grand Lodge attempted to obtain

recognition on an individual basis within the same State, they would be faced

with the mainstream requirement that candidates for recognition must be

autonomous. It has been claimed that the NGL would permit individual PHO Grand

Lodges to exchange recognition with other Grand Lodges, but the issue is fraught

with difficulty and needs further clarification.

A PHO Grand Lodge seeking recognition outside the US would have much the same

difficulty, but perhaps with a greater chance of success, provided it clearly

had NGL support.

PHA and PHO

If PHA and PHO could be reconciled, it

would go a long way towards solving the vexing problem of other Black Masonic

and pseudo-Masonic groups (see below), as well as easing the way for mainstream

recognition of the NGL, but the greatest benefit would be the redirection of

effort currently wasted on feuding with each other. Two options may be

considered:

If PHA and PHO could be reconciled, it

would go a long way towards solving the vexing problem of other Black Masonic

and pseudo-Masonic groups (see below), as well as easing the way for mainstream

recognition of the NGL, but the greatest benefit would be the redirection of

effort currently wasted on feuding with each other. Two options may be

considered:

- merger of PHA and PHO

- exchange of recognition between NGL and PHA

Grand Lodges.

Both are difficult to achieve.

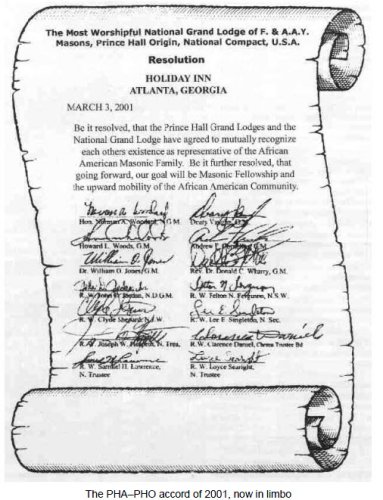

In 2001, thanks to the behind-the-scenes efforts of a small group of

peacemakers, there was a meeting between the National Grand Master and his

‘cabinet’ (PHO) with five influential Grand Masters of PHA Grand Lodges. Those

who arranged the meeting hoped for a merger, but the best that could be achieved

was a resolution of goodwill, a precursor to recognition.[7]

But the meeting was not between equals; the National Grand Master could bind the

NGL, but the five PHA Grand Masters had no authority to bind the rest of the PHA

Grand Masters. When the resolution was presented to the annual conference of PHA

Grand Masters, it was passed to a committee for consideration. Following the

committee’s report, the conference voted for a merger, in terms which would

prove unacceptable to the NGL, and there the proposal rests, in limbo.

The problem with a merger is the inequality of the two parties, on the one hand

a National body with affiliated state units, and on the other hand 47

independent bodies. The PHA Grand Lodges are unlikely to submit themselves again

to a National Grand Lodge, even though their greater numbers would ensure strong

representation on the NGL. And for the alternative of PHO Grand Lodges merging

with their PHA counterparts on terms of equality, the NGL itself would have to

be dissolved.

Recognition of the NGL would require at least the unanimous agreement of the 27

PHA Grand Lodges where there are PHO lodges or Grand Lodges—and possibly the

approval of the other PHA Grand Lodges as well. Some other formula for

reconciliation must be devised.

Prince Hall and the ‘bogus’ groups

Some of the Grand Lodges classified as

‘bogus’ appear to be regular in conduct, and autonomous, lacking only the

regularity of origin demanded by mainstream Grand Lodges—and therefore by Prince

Hall Grand Lodges also. The Prince Hall fraternity is so carefully orthodox and

conservative that it is unlikely to devise a way to ‘forgive’ this lack of

regularity of origin, unless mainstream Grand Lodges have demonstrated an

applicable variation of their own requirements in this regard. Consequently, a

merger with such a ‘bogus’ Grand Lodge, or recognition of it, is unlikely.

Individual members of such ‘bogus’ groups, if their personal qualifications meet

Prince Hall criteria, are often ‘healed’ into a Prince Hall lodge (PHA or PHO),

and sometimes a whole lodge of a bogus group is ‘healed’ and formed into a

Prince Hall lodge. This is a piecemeal ‘saving’ of good Masonic material.

The question of what to do about ‘bogus’ groups in general, and the charlatans

and rogues among them in particular, is best left to the Prince Hall fraternity

to devise solutions.

Conclusion

We who belong to the mainstream Grand

Lodges outside of North America have a part to play in bringing justice to our

segregated black brethren in North America. To those of Prince Hall Affiliation

whose Grand Lodge has exchanged recognition with the mainstream Grand Lodge in

the same State or Province, we can meet them more than half way, offering

encouragement to exchange recognition with our Grand Lodges and to participate

more fully in our universal brotherhood. And to those to whom recognition is

denied by the mainstream Grand Lodge in their own State, we can still offer the

same hand of friendship if we are prepared to reject the territorial practice

invented by the US mainstream Grand Lodges and supported by the United Grand

Lodge of England—in other words, if we follow the Australian precedent.

With regard to the brethren of Prince Hall Origin, who are in the double bind of

requiring permission from so many other Grand Lodges, both mainstream and PHA,

before they can obtain a single agreement of recognition from any Grand Lodge in

North America or by the United Grand Lodge of England, we could circumvent that

by following the Australian precedent.

It appears that we cannot directly assist in bringing accord between PHA and PHO

brethren, but acceptance of the regularity of the National Grand Lodge by our

Grand Lodges, as demonstrated by the act of recognition, could encourage such an

accord. As for those men who believe and act as Masons ought, but lack the

direct and clear descent from African Lodge of Boston, our interaction with PHA

and PHO brethren might help to bring them within the fold also.

May brotherly love prevail!

| ![]()

Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()