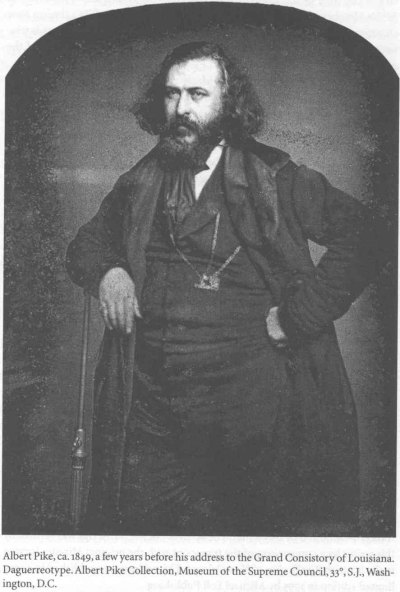

|

I

believe readily that you did not want the office, but the office wanted you

Charles

Laffon de Ladebat to Albert Pike [i]

THE

PASSAGE OF YEARS can sometimes elevate a historical figure into a legend. This

is not always beneficial when a study of the individual is desired. A historical

figure can be examined and their actions understood from a human perspective. A

legend, however, can take on near supernatural qualities and the whole of their

activities are sometimes not expected to be understood, explained or completely

recounted. Such is, at times, the case with Albert Pike. It is often difficult

to imagine Albert Pike as a player ( rather than as the player) in American

Scottish Rite events of the 1800s. The monumental mark that Pike left on the

Southern Jurisdiction can mask the fact that his influence was not always as

profound as it was in his later years. Regardless of his many accomplishments,

there was a time when Illustrious Brother Pike was but an inexperienced, yet

promising Mason with a blank book before him upon which it was unknown exactly

what would be written.

This

address, the first ever given by Pike as the presiding officer of a Scottish

Rite body, gives us a rare look at the early Albert Pike. While in his later

years, Pike was viewed by many as a true Master of the Scottish Rite, this

address clearly calls into notice his immaturity in the Rite, and he asks for

"lenient judgment" upon his

"shortcomings". In his address Pike is clearly humble and sincerely

appreciative of his election. He also notes that his election to the position of

Commander in Chief was "politic" in nature and due to

"circumstances that surround us". What could have caused a political

election of the untried Albert Pike as the presiding officer of the Grand

Consistory of Louisiana? Let's look at the "circumstances".

THE

TURMOIL THAT WAS LOUISIANA MASONRY

Just

seven years prior to Pike's assuming the leadership of the Grand Consistory of

Louisiana, the whole of Louisiana Masonry underwent a dramatic shift in

direction, leadership, and character. The once French dominated Grand Lodge of

Louisiana became "American" in nature. This shift mirrored the

cultural changes taking place in New Orleans and other French areas of the

state. Louisiana was founded as a French colony.

Even after the territory became a state in 1812, the French influence was

the dominate force, especially in the city of New Orleans. Not only was the

Grand Lodge of Louisiana a French-speaking body, but so were the five lodges

that created it. Louisiana was the most "foreign" Grand Lodge (as well

as state) in the U.S. Over time, many did not view this as an acceptable

situation.

By

the 1830s, Louisiana Masonry, as well as the whole of the Louisiana culture,

began feeling intense pressure to become "more American". With many,

this was not a welcome change. Bitter disputes and unyielding divisions

developed that culminated in actual violent clashes between the

"Creoles" and "Americans" in the downtown New Orleans

streets. The Grand Lodge was not immune to these cultural divisions which often

manifested themselves in the different rites worked by the Louisiana craft

lodges. For the most part, the French interests were championed by the lodges

working the French or Modern and A.&A.S.R. Rites and the American interests

by the York Rite (American Webb) lodges. The 1844 Constitution of the Grand

Lodge of Louisiana was the last straw for many York Masons. The new

constitution officially recognized the, then, three rites working in Louisiana

and sanctioned the creation of a "chamber of Rites" to supervise the

work of the lodges. The York position was that there should be only one

recognized rite for Louisiana craft lodges (York Rite ) and that the Grand Lodge

should be made to conform to the same system as worked by the other U.S. Grand

Lodges.

A

committee of English-speaking York Rite Masons, frustrated by the lack of

accommodation they perceived in the Grand Lodge, approached the Grand Lodge of

Mississippi and submitted a letter of grievance on January 23, 1845. [ii]

They charged the Grand Lodge of Louisiana with irregularity due to its practice

and acknowledgement of various craft lodge rituals. After debate, the Grand

Lodge of Mississippi agreed with the charges, declared the jurisdiction of the

Grand Lodge of Louisiana as "open territory" and, by 1848, chartered

seven lodges in Louisiana. [iii]

On March 8, 1848 these seven lodges formed a second Grand Lodge within

Louisiana. John Gedge, who had spearheaded the "rebellion" was elected

Grand Master of the "Louisiana Grand Lodge of Ancient York Masons".

While this new Grand Lodge received recognition from only the Grand Lodge of

Mississippi, its future was not nearly as bleak as it might seem.

The

Grand Lodge of Louisiana was created in a manner to accommodate the needs of the

lodges which organized it. The Grand Lodge was created French in nature because

this was the culture of the vast majority of those living in the area of the

Grand Lodge at that time. Over the years that followed, the Grand Lodge

continued to exist and operate in the manner in which it was created. The

majority of the membership of the lodges under the jurisdiction of the Grand

Lodge, however, changed from French to American. The Grand Lodge was then

viewed, by the majority, as not accommodating their wants and needs.

The

Grand Lodge of Mississippi received admonitions from most U.S.

Grand Lodges for their actions in Louisiana, with the majority openly

condemning its activities. [iv]

With the exception of the Grand Lodge of Mississippi, no U.S. Grand Lodge

entered into relations with the new Louisiana Grand Lodge. Regardless of their

seemingly advantageous position, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana was in serious

trouble.

The Scottish Rite Journal is published bimonthly by the Supreme Council, 33°, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry of the Southern Jurisdiction, United States of America, Washington, DC.

The Scottish Rite Journal is published bimonthly by the Supreme Council, 33°, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry of the Southern Jurisdiction, United States of America, Washington, DC.

|

Outside

of New Orleans, there were a few pockets where the French culture was strong,

but the majority of the state was already (or was becoming) Americanized. The

events surrounding the creation of the Louisiana Grand Lodge buckled the knees

of the Grand Lodge because most of the lodges under this new Grand Lodge were

located in the New Orleans area -perceived to be the largest stronghold of the

French culture within the state as well as the home of the Grand Lodge. The fact

that the Grand Lodge of Louisiana was overwhelmingly considered to be the

"regular" Grand Lodge in Louisiana was not sufficient to overcome the

internal problems stemming from the cultural divisions in New Orleans. By mid

1849, it was realized that the English-speaking lodges that had remained loyal

to the Grand Lodge were showing signs that continued loyalty would, most likely,

not happen. Contributing to the dilemma was divisions between the

French-speaking New Orleans Masons.

Obviously

realizing that the total collapse of the Grand Lodge of Louisiana was a very

real possibility, the Grand Lodge and the Louisiana Grand Lodge, A. Y.M. entered

into discussions in 1849 designed to merge the two bodies. [v]

That merger took place in June of 1850 with the approval of a new Constitution

of the Grand Lodge of Louisiana of Free and Accepted Masons. Under the terms

of the agreement of the merger, the Louisiana Grand Lodge, A. Y.M. members

declared "irregular" would be healed by the Grand Lodge of Louisiana,F.&A.M..

All Lodges chartered by the Louisiana Grand Lodge, A. Y.M. ( or by the Grand

Lodge of Mississippi in Louisiana) would, also, pass under the jurisdiction of

the new Grand Lodge of Louisiana, F.&A.M. John Gedge, who had served as

Grand Master of the Louisiana Grand Lodge, A. Y.M., was elected Grand Master of

the new Grand Lodge of Louisiana, F.&A.M. for 1851.

While

this new constitution seemed to merge the two Grand Lodges, the Grand Lodge of

Louisiana was, in reality, replaced by the Louisiana Grand Lodge, A. Y.M.. All

that actually remained of the old Grand Lodge was the name, organizational date

of 1812, and the list of Past Grand Masters. The nature of the new Grand Lodge

of Louisiana, F.&A.M. changed to match the Louisiana Grand Lodge, A. Y.M..

The "Americans" were in power.

The

old Grand Lodge of Louisiana officially accommodated lodges working in the York

(American Webb), French, or Modern, and A.&A.S.R. craft rituals. The

French-speaking Masons believed that the two Grand Lodge merger would result in

the continued recognition oflodges working in all three rites. They were

horrified and outraged when the new Grand Lodge instructed all non-York Rite

lodges to turn in their charters so that York Rite charters could be issued. [vi]

Charges of trickery abounded. Three A.&A.S.R. craft lodges (Etoile Polaire,

Disciples of the Masonic Senate, and Los Amigos del Orden) applied to the

Supreme Council of Louisiana for relief. The Supreme Council announced that

since the Concordat of 1833 between the Grand Lodge of Louisiana and the Grand

Consistory of Louisiana (at that time the highest ranking Scottish Rite body in

the State) had been violated by the new Grand Lodge, the Supreme Council would

issue charters to these lodges and allow them to pass under its jurisdiction. [vii]

The

French Rite Masons did not have a Grand Body from which to seek relief. The

Grand Lodge had been the "home" of the French Rite. With no superior

body for the government of the French Rite lodges, they would, ultimately,

disappear from Louisiana Masonry as an identifiable force. [viii]

THE

SETTING FOR MORE CHANGE

When

we step back and attempt to look at the situation through the eyes of the

participants, we can see that the Supreme Council of Louisiana taking

jurisdiction over the three A.&A.S.R. Craft Lodges must have been just as

jarring to the new Grand Lodge of Louisiana as the action of the Grand Lodge of

Mississippi was to the old Grand Lodge. No one could see or know the future. The

Grand Lodge of Mississippi had been a body in full fraternal relations with the

old Grand Lodge, as was the Supreme Council of Louisiana. While the Grand Lodge

of Mississippi was a sister Grand Lodge, the Supreme Council of Louisiana was

composed of members who were nearly all Grand Lodge officers, a good number of

whom were Past Grand Masters. The Supreme Council of Louisiana was not an

insignificant body. The actions of the Grand Lodge of Mississippi set into

motion a series of events that led to the downfall of the old Grand Lodge of

Louisiana. It was not unfeasible for the actions of the Supreme Council of

Louisiana to result in the same fate for the new Grand Lodge of Louisiana.

Clearly this situation needed to be addressed by the new Grand

Lodge.

At

the invitation of Grand Master John Gedge, Albert Mackey came to New Orleans in

1852 and established, for the Charleston Supreme Council, a Consistory of the 32°.

Gedge was appointed Commander in Chief of this new consistory. Obviously, the

Supreme Council of Louisiana charged that this was an outrageous invasion of

territory. Not only was it the fact that the Consistory was organized in New

Orleans, but the manner in which it was created was the subject of severe

criticism. In 1853, Charles Laffon de Ladebat wrote about the events concerning

the new Grand Lodge, the Supreme Council of Louisiana and the new Charleston

Consistory in New Orleans.

In presence of such despotic, anti-masonic conduct, the Scotch BB:.

resited as men, as Masons, and formed an independent corporation under the only

M:. authority existing in Louisiana dejure et defacto. The balance remained with

the new Grand Lodge, swore obedience to her, through indifference rather than

from conviction. Soon after this, the very same Sectarian, in his restlessness,

caused Br :. Albert G. Mackey to come from Charleston, in order to establish a

Grand Consistory, exactly as if there never had existed a Supreme Council of the

Scotch Rite in Louisiana. Our sectarian, after abolishing the Scotch Rite,

wished to re-establish it in order to be at the head of it. This Consistory has

been inaugurated, you know it M:. W..., for you were admitted into it for proper

causes. The manner in which the degrees were conferred in this spurious

Consistory is and will be an eternal shame to the Br :. who has conferred them. [ix]

While

we can only speculate as to the events which might have caused this

"eternal shame" statement, it is evident that the creation of the

Charleston consistory in New Orleans fanned the flames of emotion and deeply

angered the already frustrated NewOrleans Scottish Rite Masons. But what could

be done?

The

cultural variances within New Orleans societies during the 1800s are far too

complex to be explained from onlya French and/or American viewpoint. New Orleans

was a cosmopolitan city with layers of cultures and subcultures. The lodges

under the Grand Lodge of Louisiana were not only French and English speaking,

but there were also lodges working in German, Italian, and Spanish. Like the

many New Orleans neighborhoods, Masonic lodges often reflected the culture of

the members of the lodge. Prior to 1850, the Grand Lodge maintained but a

minimal supervision of the lodges under its jurisdiction. As long as a lodge

worked within a general Masonic framework, as defined by the Grand Lodge, the

lodge was left effectively alone. For some lodges (especially in rural areas)

the only contact they had with the Grand Lodge was when they sent in their

yearly returns. Lodges were free to develop their own cultural "stamp"

on both their lodge and the ritual they used. Germania Lodge No.46 was created

as a German-speaking lodge receiving a York Rite charter from the Grand Lodge of

Louisiana in 1844. Their 1844 ritual shows that they originally worked an

eclectic ritual which may well have derived from all three rites worked in

Louisiana (as well as rituals from outside the state). [x]

It is very possible that the unknown author(s) of this ritual simply sat down

with a number of rituals and created a unique ritual to his (or their) liking.

Such independent activity was not uncommon.

The

freedom extended to the lodges by the Grand Lodge may have ultimately

contributed to the downfall of the French interests in Louisiana. The York Rite

English-speaking Masons were, by then, in the majority, but it was not a large

majority. The non-York Rite Masons might have been able to overturn the actions

of the new Grand Lodge, but they could not unify themselves and were split into

unyielding factions with their own goals and agendas.

Regardless

of the influence the Supreme Council of Louisi'ana once had in Louisiana, the

creation of the 1852 Charleston Consistory created a split that led to the

demise of the New Orleans Supreme Council as a true Masonic power. Not only was

the New Orleans Council locked in battle with the new Grand Lodge, it was also

facing perplexing (in NewOrleans) charges of irregularity -charges that it was

not prepared to answer. The rapid fire changes involving the whole of Louisiana

Masonry left most of the French Masons flabbergasted and hopelessly divided as

to which direction to take. It was at this time that a new "solution"

was introduced that cut the divisions even deeper.

THE

CONCORDAT OF 1855

The

Scottish Rite in New Orleans existed in what might be described as a

"parallel universe" with the rest of the U.S. A.&A.S.R. Given the

cultural difference between the whole of Louisiana Masonry and the rest of the

U.S., the differences and "detached" nature of the Scottish Rite in

New Orleans is understandable. With the "American invasion" of

Louisiana Masonry came a forced realization that changes would have to be made

in the nature of all Louisiana Masonic bodies. Exactly what changes would be

necessary was the subject of heated debate.

The

creation of the 1852 Mackey/Charleston Consistory in New Orleans triggered

intense emotion in an already explosive environment. It was during this time and

in this setting, that a plan to merge the Charleston and New Orleans Supreme

Councils was born. For those who viewed the New Orleans Supreme Council as the

only hope of preserving the French interests in New Orleans, the idea of such a

merger was wholly unacceptable. The more moderate French Masons saw such a

merger as, quite possibly, the only option left. In 1860, Charles Laffon de

Ladebat wrote to Albert Pike about the Concordat and explained his position of

it.

My resolution of retiring from active practice is 5 years old & more.

Hear what I wrote to Mackey January 31,1855: "When the work will be

accomplished, when every thing will be in proper order & well understood,

will retire willingly & leave the management of all to more competent, but

not more devoted hands". We know that the foreign influence will & must

be superseded by the American element. Now the time has come & I believe

that, even in Masonry, Americans must rule in America. I, a frenchman, must

retire -in due time. [xi]

Not

all of the French Masons were willing to turn over what they viewed as their

"possession" to others with different ideas, plans, and goals. When

the merger between the two councils seemed to be inevitable, the officers and

nearly half of the Active Members of the New Orleans Supreme Council resigned

rather than take part in the Concordat. On January 7, 1854, the remaining

Members of the council elected Charles Claiborne as the new Grand Commander,

Claude Pierre Samory as Lt. Grand Commander, and Charles Laffon de Ladebat was

appointed Grand Secretary. The Concordat merging the Charleston and New Orleans

Supreme Councils was signed in New Orleans on February 16, 1855. The New Orleans

Supreme Council ceased to exist as a Supreme Council and the Grand Consistory of

Louisiana merged with the 1852 "Mackey" Consistory.

With

the Concordat of 1855, the elimination of the French control of Louisiana

Masonry was complete. The unrest, dissatisfaction, and ill feelings, however,

continued to fester. James Foulhouze was the Grand Commander of the Supreme

Council of Louisiana who, along with the other officers, resigned from the

council rather than participate in the Concordat. Claude Samory and AlbertMackey

approached Foulhouze in the summer of 1856 to enlist his aid in healing the old

wounds and to, hopefully, rebuild the A.&A.S.R. in New Orleans. Foulhouze

was offered the office of Commander in Chief of the Grand Consistory of

Louisiana and Active Membership in the Charleston Supreme Council if he would

join in the rebuilding. Foulhouze declined the offers and began his efforts to

reorganize the New Orleans Supreme Council with its former officers.[xii]

With

James Foulhouze out of consideration, a new leader for the troubled New Orleans

Scottish Rite had to be found. The choice would prove to be inspired.

ENTER

ALBERT PIKE

Albert

Pike was an attorney by profession and a Mason of only five years when he moved

his law practice to New Orleans in 1855.[xiii]

Thro years earlier, Pike received the Scottish Rite degrees up to the 32° from

Albert Mackey in Charleston. Mackey saw a unique quality in Pike and recruited

him to be on the ritual committee of the Charleston Supreme Council. Mackey lent

Pike a collection of Scottish Rite rituals for his review and study. It was

through the examination and transcription of these rituals that Pike received

his first understanding of the A.&A.S.R. Busy with setting up his law

practice and studying the rituals lent to him by Mackey, Pike did not concern

himself with the momentous developments taking place in New Orleans at the time

of his arrival.

One

of Pike's earliest Masonic acquaintances in New Orleans was Charles Laffon de

Ladebat. Over the years ( even after Pike became Grand Commander) these two

would maintain a "love/hate" relationship that was founded on a basic

respect for each other. Ladebat was made a 33° by James Foulhouze in the New

Orleans Supreme Council on February 11, 1852, and served as its Grand Secretary

at the time of the Concordat of 1855. Ladebat would later be elected an Active

Member of the Charleston Supreme Council in 1859. Pike's time in New Orleans put

him in close contact with many competent New Orleans 33rds who were quite

capable of completing Pike's education and understanding of the A.&A.S.R.

Ladebat was, clearly, one of Pike's early mentors.

Just

as he had done with Albert Mackey, Pike greatly impressed the New Orleans

Scottish Rite Masons. Pike's talent and raw abilities clearly made him a

candidate for any Masonic office. The fact that Pike played no part whatsoever

in the Concordat of 1855 may have made Pike even more attractive and a prime

candidate for leading the Grand Consistory of Louisiana. Pike did not carry

"baggage" with him from the Louisiana Masonic turmoil. While he was

under the jurisdiction of the Charleston Supreme Council at the time of the

concordat, he was not an Active Member and played no part in any of the

decisions concerning the Concordat. No one could "blame" Pike for any

of the events. Albert Pike was the only serious candidate for leading the Grand

Consistory who could be seen as potentially objective as well as extraordinarily

promising. Next to James Foulhouze, no one had a better chance of appeasing the

French Masons and unifying all the factions. Once the New Orleans Supreme

Council was re-organized, Pike's value to the "Charleston cause" was

even more evident.

This

address, given by Pike only four days after he received the 33°, [xiv]

is valuable to all Scottish Rite researchers not only because it is an extremely

rare piece of early Pike literature, but also because of significant information

provided in it. From this address we not only get abetter feel of the early

Albert Pike, but also have the opportunity to develop a more detailed

understanding of the momentous events that were taking place at the time Albert

Pike arrived on the Scottish Rite stage. Within just two years from the time of

this address, Pike would be elected an Active Member of the Southern

Jurisdiction (over the possible objections of the Grand Commander and Lt. Grand

Commander) [xv] and then on January 2,

1859, with the very first S.J. election of officers, be elected to the position

of Sovereign Grand Commander.

Pike's

address was ordered to be recorded in the handwritten Minutes of the Grand

Consistory of Louisiana. A typed transcript of this address was made by an

unknown Brother sometime between the 1940s and 1950s and a copy of this

transcript acquired by this writer. The accuracy of the transcript was verified

by this writer by a comparison of the transcript with the original Minutes

located in the Scottish Rite Bodies of New Orleans. This address was published

in a very limited edition in 1995 by Michael Poll Publishing.

ADDRESS

BEFORE THE GRAND CONSISTORY OF LOUISIANA

ADDRESS

BEFORE THE GRAND CONSISTORY OF LOUISIANA

ALBERT

PIKE

Apri1

29 1857

Th

:. Ill:. Bros :. and Sublime Princes of the Royal Secret:

I

PRAY YOU TO ACCEPT MY MOST SINCERE THANKS and profoundest gratitude for the

great and unexpected honor which you conferred upon me, when, in my absence, you

selected me to fill the most honorable and very responsible station of Grand

Commander of this Grand Consistory and for your present ratification of that

choice. I will earnestly endeavor to have myself not wholly undeserving of your

good opinion; so that, although it must now be said that when elected I was not

worthy either by service or qualification, it may not hereafter be said that

when I cease to serve, you repented of your selection.

I

can bring to your service, Princes, little more than good intentions, kind

feelings, and a zealous devotion to the interest of Masonry of all Rites -when

you find me deficient (and wherein shall I not, alas, be found, Bro :. ? ) I

entreat of you in advance lenient judgment upon my short-comings, and that you

will kindly aid me with your sympathy, support and advice. For I must be ever

embarrassed by the reflection that I have been by your too favorable judgment

preferred to many eminent and distinguished Brethren, whose longer service and

greater familiarity with the work gave them far higher claims than any I could

have preferred to the post of honor and command. If I supposed that personal

consideration or a belief in my superior fitness and capacity had led you to

this choice, I should sink under a sense of my feebleness, not ever have

succeeded in overcoming my repugnance to accept a post where so much was to be

expected. But, amass that there were other reasons, which acted upon you, and

made your selection seem politic and for the interest of Masonry in this Valley,

reasons not personal to me, but growing out of the conditions of things and the

circumstances that surrounded us. I am encouraged to hope that I may in some

degree aid in attaining the result which you all desire, and that your just

expectations may not be disappointed.

I

have accordingly accepted tile post which you have tendered me, and will

endeavor to perform its duties. Most important private business will compel my

absence for some months. I shall return as soon as practicable, and remain

thereafter permanently in the city. [xvi]

Should

the interest of the Order at any time be likely to suffer by my temporary

absence, I shall be prepared at once to surrender up my office, faintly

imitating the lofty magnanimity, of which so beautiful an example has been set

me by an Ill:. Bro:. whose genius and labors have done so much to restore the

splendors of the Ancient and Accepted Rite [xvii]

in this Valley, and whose name will not be forgotten among us, while the order

of Knights Rose Croix continues to exist, or the Kadosh to war against tyranny

and usurpation.

But

I shall most sensibly feel how great will be the contrast between myself, with

my slender experience, and the Th:. Ill:. Prince and Sovereign whose place I

come to take, but not fil.[xviii]

Eminent in Masonic learning and more illustrious by long and faithful service

than even by his high rank and lofty station, the new and supreme dignity

recently conferred upon him was a most just and appropriate acknowledgment of

his worth. This Consistory must most sensibly feel its loss, as he, Ill:. Gr :.

Commander, crowned and laurelled with the highest honor, and with the grateful

thanks and recollections of his brethren, most gracefully retires from this

distinguished post, to yield it of his own choice to another. I beseech him not

to withdraw from me his counsel and advice, and I pray him and our Ill:. Bro:.

Laffon, [xix]

and the other eminent brethren who surround me, to aid me, to advise me, to

support me in my inexperience, that, guided by them I may not despair of

rendering some little service to the cause of humanity, to the cause of truth,

of liberty, of philosophy, and of Masonic progress.

My

brethren, I see around me the representatives of more than one race, [xx]

and the disciples of more than one Masonic Rite -I rejoice at this reunion, and

it gives me happy augury of the prosperity, health, and continuance of Masonry

in this Valley. I am especially glad that here and in other bodies of this Rite,

I see by the side of the children of the first generous and gallant settlers of

Louisiana, many of another land, and who not long since for the first time

passed beyond the boundaries of the York Rite.

We

are all aware, my brethren, how little among Masons of the latter Rite is known

of the Ancient & Accepted Rite, and how great and general a prejudice has

obtained those against it. It has been imagined that there was antagonism

between the two: Scottish Masonry has been deemed almost spurious, and its

degrees, at the best, no more than mere side degrees; and the York Mason who has

entered into our sanctuaries has been regarded in the estimation of many, as

untrue to his allegiance and disloyal.

Those

of you, my brethren, who lately have known only the York Rite, are already aware

how unfounded is this prejudice, how erroneous this opinion, how chimerical

these apprehensions and alarms. It shall be my study to make you more fully to

know this hereafter.

The

Ancient and Accepted Rite is, when itself fully developed and understood, when

itself what it should be and can be, a great, harmonious and connected system,

all the degrees and lessons, embody the philosophy, the history, the morality

and the essential meaning of Masonry, and are to us what the Ancient mysteries

were to the initiate of Eleusis, of Egypt, and of Samothrace.

The

degrees of this Rite are commentaries on the Master's Degree, which itself is

essentially the same in all Rites. They interpret instead of being at variance

with that degree. They ultimately make it known to the Initiate the true word

and the true meaning and inner sense of the True Word of a Mason. They teach the

great doctrines that God taught the Patriarchs, and which are the foundations on

which all religions repose.

We

do not undervalue symbolic Masonry, nor love it the less because we also love

the Ancient & Accepted Rite, we but learn justly to value the Master's

degree, by coming to understand its full meaning and to appreciate the sublime

and lofty lessons which it teaches. Masonry is one everywhere and in all its

Temples of whatever Rite; as it has been one in all times. Everywhere it teaches

the same great lessons of morality and philosophy, or should do so, if faithful

to its mission, and if its apostles are properly informed and true to the duties

which it imposes on them. If anywhere it has excluded from even the inmost

Sanctuaries of its Temples men of any faith who believe in Our Supreme God,

Creator and Preserver of all things that become, and in the immortality of the

Soul-if it has anywhere assumed the garb of religious exclusion and intolerance,

of Jesuitism, of political vengeance, of Hermetic Mysticism, there most

assuredly it has ceased to be Masonry.

It

would not be true to say, however, that even Scottish Masonry has adequately

fulfilled or been equal to its missions. While by the irresistible influence of

time, by innovations and by mutilations and corruptions of ignorance, the

degrees of the York Rite have long since ceased to be what they should be, and

what they were in the beginning, when they succeeded to those ancient academies

of science, philosophy and morality, the mysteries; while the practice of

confirming everything contained in them to the memory has by the silent lapse of

time caused more and more both of ceremony and substance to be forgotten, much

to be intentionally dropped, and the field of each degree to be made more and

more narrow; while the true meaning of very many of their most valuable symbols

have faded away and disappeared, and been replaced by commonplace, and the

inventions of ignorance, and the lofty science and profound teachings, of the

Ancients have too much given way to unimpressive phrases and valueless formulas,

-the Scottish Rite also has not enjoyed immunity from the ravages of the biting

tooth of time, universal destroyer of all human beings.

For

even here, where over the Temples of our Degrees stood perfect and complete in

all the splendor and Majesty of their beautiful and harmonious proportions, we

are like strangers from a far land who wander amid the shattered columns and

wrecked glories of Thebes and Palmyra, and union over the ruins that track the

steps of time, and over the instability of all earthly things. From many of our

degrees everything has dropped out except the signs and words, and they remain

half effaced and corrupted. From more, all is lost except these and some

unimportant formulas; in still more, useless repetition arrives at

impressiveness, but cannot renunciate us for the old science and the noble

philosophy whose place it endeavors to supply. Those huge chasms have been

created in the work, and the connections between the degrees have been broken;

so that each has become a fragment instead of being, as at first part of one

consistent, regularly progressive and harmonious whole.

Thus

it has come that of the degrees from the fourth to the thirty-second inclusive,

which we retain and apply to ourselves the sounding titles, four only are

habitually conferred, which all the residue remain in a great measure, and part

of them altogether unknown.

It

had become so obvious that this Rite needed reformation, and that either its

degrees should all be made worthy to be conferred and of value to be attained,

or else those which were not so ought to be abandoned and their titles disused,

that more than two years ago the Supreme Council at Charleston appointed a

Committee of five Brethren to revise the whole ritual of the degrees; on which

Committee I had the distinguished honor to be placed. While my Brother Laffon,

both before and after he was also placed there in the stead of my Brother Samory,

who to the general regret found himself compelled to decline the act. [xxi]

While my Brother Laffon labored, more particularly on the 18th Degree, but not

alone on that, I also, undertaking at first a few degrees, continued my labors

during two years, until I completed a revision of all; which that it may be

thoroughly examined and sanctioned, I have printed in a volume and submitted to

the Supreme Council. Whether that August Body will stamp it or any part of it

with its approval, is wholly unknown to me. I have endeavored to restore the

effaced or faded lineament of many of the degrees to develop and elaborate the

great leading idea of each, to correct the whole together as a regular series,

and to make of them our harmonious and systematic whole, ascending by regular

graduations to the highest moral and philosophical truth -I have endeavored to

prime away all commonplaces and puerility's, all unmeaning forms and ceremonies,

all absurd interpretations, and everything useless or injurious with which time

and ignorance had overloaded the degrees. I have endeavored so to restore, to

retouch and to supply, retaining all that was valuable and working up all the

old material, as to make every degree worth to be conferred: that there should

be no longer any empty tile, or barren honors in the Ancient & Accepted

Rite.

This

I have attempted; but I am only too well aware that the undertaking was too

great for my furios; and that what I have done will be found full of

imperfections, as the work of the painter, the sculpture, the creator, and the

poet ever falls short of his own ideal.

Still

I have endeavored to do somewhat; and it is my desire, at some appropriate

future time, and with your consent and assistance, to confer upon some suitable

candidate such of the degrees, as I have revised them, as have not been already

revised by other and more competent hands.

I

congratulate you, my brethren, on the advancement and progress of the Ancient

& Accepted Rite in this Valley: The Concordat by which the Supreme

Jurisdiction of the Supreme Council at Charleston was acknowledged and under

which the two Consistories then existing became one, laid broad and deep the

strong foundations of the prosperity of our Rite. The walls of our TempIe,

solidly and squarely built, bid defiance to the storms of faction; and if we are

true to ourselves, peace will dwell within our gates.

And

in the Realm of Masonry, if anywhere on earth, there ought to be peace ahd quiet

and harmony. No where are schism and faction, and disunion and discontent so

lamentably out of place as here. Here there should be no lust for power and no

eagerness for rank or distinction. If discontented men should in this valley

have established, or if any shall hereafter establish, under a foreign authority

which has no jurisdiction here and act only by usurpation, any body or bodies,

claiming to administer the Ancient & Accepted Rite, we shall, I think, be

prepared to show that the Supreme Council at Charleston, to which we owe

allegiance, is the only legitimate authority in the Rite that can exist in our

country south of the River Potomac; and that the Grand Orient of France and the

Supreme Council within its bosom offered against Masonic Law and Masonic Comity

where they made another jurisdiction and erect their banners on the soil of

Louisiana.

It

is time that this question should be receive the fullest consideration; and that

the authentic history of the creation of the Grand Orient itself and of that of

the Supreme Council of France, of the disputes between those two bodies and

their temporary alliance should be made known to the order in the United States.

Supplied with the emissary documents on both sides, it is every intention to

translate them and make them public, that all may judge where is the right and

where the usurpation.

The

time when fables would pass for history has gone by; and that has come when

criticism and investigation will deal with the history of Masonry as with other

histories, separating the truth from the error, and after reducing great

pretensions to the narrowest proportions. Let us examine the history the Ancient

& Accepted Rite and the Grand Orient in that spirit and by the rules and

canons of sound criticism, never forgetting that courtesy, moderation, and

kindness ought to inspire all Masonic discussions, hoping to find a like tone

and spirit on the other side, and that those who may array themselves against us

will, if Right and Truth be found with us, candidly admit it, and uniting with

us acknowledge the same allegiance and so cause peace ever and ever to reign in

this valley.

My

Brethren, let me impress it upon you, that there is much to do, if we would have

Masonry adequately fulfill its mission. It is not sufficient merely to receive

three or four of the degrees, and then, imagining the rest, to live in contented

indolence, without an effort to know the high science and philosophy of the

system. The time has come when one who would be truly and really be a Scottish

Rite Mason must study and reflect. It shall be my earnest endeavor to aid you in

penetrating to the inmost heart of Masonry and in unveiling its profound

secrets, which are that light towards which all Masons at least profess to

struggle, that knowledge of the True Work which is the great remuneration of a

Mason's labor. But if I should fall short of the performance of this duty, be

not you, my brethren, disheartened nor discouraged. Masonry must be true to

itself, or it will find in numbers weakness only, and its walls will be crushed

to the ground with its own might. In this intellectual and practical age..

Masonry must it from merited disaster and dissolution.

It

is time for it to assume a higher ground; and here, if any where, the effort to

elevate it must be made. Here, I believe, we can commence and successfully carry

onward the indispensable work of reformation, that shall in time end the reign

of puerility's and trivialities, and make masonry what it should be. The great

teacher of moral and philosophical truth; the teacher of the primitive religion

known to the first men that lived; the defender pf the right of free thought,

free conscience and free speech; the apostle of rational and well regulated

liberty; the protector of the oppressed, the defender of the common people, the

asserterof the dignity of labor and the right of the laboring man; the enemy of

intolerance, fanaticism and uncharitable opinion, and of all idle and pernicious

theories that arraign providence for its dispensations, and endeavor to set

their notions of an abstract justice and equality above the laws by which God

chooses to rule all human affairs.

In

this great work I wish your co-operation, and I ask, for myself and for those

eminent brethren who are to act with me and in my place, your countenance, your

assistance, and your encouragement. I am sure my brethren that I shall not ask

this in vain; and that grateful, deeply grateful as I now am for your confidence

and kindness, I shall be far more so, and with far greater reason, when I am

allowed to surrender into your hands the trust which you have so generously

confided to me.

NOTES

[i]

Charles Laffon de Ladebat to Albert Pike, Iun. 24, 1860. Archives of the

Supreme Council, 33°, S.I., Washington. Photocopy in possession of the

author.

[ii]

Report of the Committee on Foreign Correspondence of the

Louisiana Grand Lodge of York Masons (New

Orleans: Cook, Young & Co., 1949), p. 5.

[iii]

George Washington, Lafayette, Warren, Marion, Crescent City, Hiram, and

Eureka.

[iv]

Grand Lodge of the State of Louisiana Report and

Exposition (New Orleans: I. L. Sollee, 1849),

pp. 5-34.

[v]

James B. Scot, Outline of the Rise and Progress of Freemasonry in Louisiana

(1873; reprint, New Orleans: Michael Poll Publishing, 1995), pp. 78-80.

[vi]

Charles Laffon de Ladebat, A Letter to H. R. W. Hill, Grand Master of the

Grand Lodge of Louisiana, Concerning the Schism between the Scotch & York

Rites (New Orleans: J. Lamarre's Printing Office, 1853), pp. 7-8.

[vii]

Scot, Outline, pp. 86-87.

[viii]

An attempt was made in the late 1800s to revive the French Rite in New Orleans

through the short lived Grand Orient of Louisiana. This body was

created in 1879, but, possibly due to little support, did not last longer than

ten years. See: Proqres

Grand Orient de la Louisiane (Rite Moderne) (New Orleans: P. & E.

Marchand, 1886) . A

copy of this very rare work is in the George Longe Papers in the Amistad

Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans.

[ix]

Ladebat, Letter to Hill, pp. 7-8.

[x]

Art de Hoyos, Introduction, The Liturgy of Germania Lodge No.46, R&A.M.

(New Orleans: Michael R Poll, 1993).

[xi]

Ladebat to Pike, Jun. 24,1860.

[xii]

See: Michael R. Poll, "James Foulhouze: Sovereign Grand Commander

of the Supreme Council of Louisiana;' Heredom, vol. 6 (1997), pp.

49-82.

[xiii]

Pike's law office was located in downtown New Orleans in a building on the

riverside of Camp Street one block from Canal Street. The building no longer

exists. New Orleans City Directory, 1856.

[xiv]

After the Concordat of 1855, the Active Members of the New Orleans Supreme

Council were brought in as Honorary Members of the Charleston Supreme Council.

As with all Honorary Members of a Supreme Council, they held the 33° but not

the active office of Sovereign Grand Inspector General (S.G.I.G.). It was at

this time that theCharleston Supreme Council began elevating 32° Masons to

the 33° but not including the office ofS.G.I.G. in their elevation. Albert

Pike was one of the first 32° in the S.J. elevated to the 33° without being

invested with the office of S.G.I.G. Pike would be elected an Active Member (S.G.I.G.)

of the Charleston Supreme Council on March 20,1858.

[xv]

". ..I was not the last to devise the means of placing you at the

head of the order, 1st by making you a 33rd against the will of Messrs. Furman

& Honour: 2nd by vacating my office of Deputy in your favor, &twice

you got in the S.C. & especially twice you were unanimously elected to the

Presidency, I consider myself as having done my duty, all I could do. The

lifeless council of Charleston was revived; it lives now! Only now tho!"

Ladebat to Pike, Jun. 24,1860.

[xvi]

The New Orleans City Directories

from 1856 unti11859 show that while Pike had opened a law office in New

Orleans, he did not have more than a temporary home in the city. The Minutes

of the Grand Consistory also reveal that he was absent for many of the

meetings of the Grand Consistory. There is no record that Pike ever moved his

family to New Orleans, and it is probable that he traveled between his home in

Little Rock and New Orleans. One of the many boarding houses in New Orleans

would have likely been his residence during his stays in the city. Despite

Pike's statement, New Orleans would never be his permanent home.

[xvii]

At the time of this address, the term Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite

was not in common use in the U.S. This accounts for Pike's repeated use of the

older (in the U.S.) term Ancient and Accepted Rite.

[xviii]

Pike refers to Claude Pierre Samory. Samory was elected an Active Member of

the Charleston Supreme Council on Nov. 20, 1856.

[xix]

Charles Laffon de Ladebat.

[xx]

Freemasonry in pre-Civil War New Orleans was reflective of the New Orleans

culture of the time. Pierre Roup was the son-in-law of New Orleans Mason and

Battle of New Orleans hero Dominique Youx. Roup was a member of Perseverance

Lodge No.4 and sat on the lodge's building committee. He was a black Creole.

While it is clear that there were more than a few black Creoles who were

members of New Orleans lodges, identifying them is difficult, as ones' race

was not a question asked or recorded except in notable situations. It is quite

possible that there were black Creole members of the Grand Consistory of

Louisiana present at the time of Pike's address. It is, likewise, possible

that Pike used the word "race" in reference to the French Masons who

were often considered part of the "Latin race".

[xxi]

On p. 249 of his History of the Supreme Council 33°, A.&A.S.R. S.J.,

U:S.A (1801- 1864) (Washington: Supreme Council, 33°, 1964) Ray Baker

Harris, 33°, reproduces a letter sent by Albert Mackey to Claude Samory dated

Mar. 21, 1855. The letter concerns the Southern Jurisdiction's Ritual

Committee and lists its members. Claude Samory is listed as the member from

New Orleans and Albert Pike the member from Little Rock. Ill. Harris writes:

"From all indications, the 'preparation of new copies' was in the hands

of Albert Pike. He was then in New Orleans, and may have conferred with Samory

in this work, but neither of them ever mentioned such a collaboration in their

numerous letters written in this period". Until this address by Pike was

rediscovered, it was assumed by most A.&A.S.R. scholars that Samory was on

this committee with Pike for a substantial period of time. Bro. Harris,

assuming that Samory remained on the committee, logically wondered about the

absence of communications between Pike and Samory concerning ritual matters.

This address brings to light the fact that Samory retired from the committee

shortly after his appointment to be replaced by Ladebat. The collaboration was

not between Pike and Samory, but between Pike and Ladebat and renders the

degrees written by the two and their ritual communications understandable.

|

![]() News Feed |

News Feed |  Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email