|

Introduction

One

of the objectives of Freemasonry, as promoted by the United Grand Lodge of

Victoria (Appendix A), is to

‘Provide opportunities for self development’.

Self-development

is the growth of the individual person’s abilities by the individual himself.

Such development can of course be greatly influenced by the people and

organisations with which the individual relates.

ANZMRC publishes a quarterly newsletter, Harashim (Hebrew for Craftsmen), which is circulated worldwide in PDF format by email.

Subscribe

Harashim.

ANZMRC publishes a quarterly newsletter, Harashim (Hebrew for Craftsmen), which is circulated worldwide in PDF format by email.

Subscribe

Harashim.

|

In

previous periods of operative masonry, the craft guilds were largely concerned

with the development of the individual as a skilled craftsman. The operative

stone mason left the ranks of Apprentice and became a Fellow of the Craft when

he was able to demonstrate that he was a skilled workman who had mastered the

requirements of his trade. With the development of speculative Freemasonry,

self-development was expanded to include a broadening of the mind, intellect and

talents in general, through education and learning, not only for individual

benefit but for the greater benefit of society in general (Information

For Fellowcraft, UGLV).

This

paper will examine the current Masonic approach to self-development, by

considering the Craft’s understanding of the world and the individual, some

streams of thought that have influenced current Masonic views, and future

implications for the Craft.

Masonic

view of the world

The

state of the world and the individual’s interpretation of it greatly affect

the range of opportunities for self-development. The unified view that

Freemasonry holds about the universe, and the individual’s place within it, is

contained in the rituals of the first, second and third degrees, and is

summarised in the Retrospect of the Third Degree (Appendix

B).

Freemasonry

perceives the universe to be composed of two dimensions, material and spiritual.

With regard to the spiritual dimension, Freemasonry takes a monotheistic view.

That is, one God is acknowledged, and is believed to exist as a distinct being,

who created the world and who works through and in the world. God also being the

ultimate basis for determining moral and good human behaviour.

Referring

to the first degree, the Retrospect

says (from line 20):

. . .

above all, it taught you to bend with humility and resignation to the will of

the GAOTU, and to dedicate your heart, thus purified from every baneful and

malignant passion, fitted only for the reception of truth and virtue, as well to

His glory as the welfare of your fellow-creatures.

As

to the material world, Freemasonry exhorts the individual to expand his

knowledge and to develop his intellectual abilities to gain understanding. As

the Retrospect states (line 27):

. . .

you

were led in the second degree, to contemplate the intellectual faculty . . .

The

Retrospect provides a very useful

outline of the Masonic approach to the material world, as it contains guidelines

for individual behaviour and self-development.

Masonic

view of the individual

The

Retrospect teaches the individual at

least five great truths concerning life:

Truth

1.

That we all enter this world helpless and dependent on others for our immediate

survival and development.

Truth

2.

That we also enter this world equal, not in terms of physical attributes or

mental abilities or material endowments, but in terms of our mortal condition.

Your

admission into Freemasonry in a state of helpless indigence, was an emblematical

representation of the entrance of all men on this, their mortal existence. It

inculcated the useful lessons of natural equality and mutual dependence . . .

[line 11]

Truth

3.

That because human beings share a common mortality and dependence upon each

other, there is the need for charity and support one another, particularly in

times of trouble or distress.

. . .

it instructed you in the active principles of universal beneficence and charity,

to seek the solace of our own distress by extending relief and consolation to

your fellow-creatures in the hour of their affliction . . . [line 15]

Truth

4.

That self-development is achieved by the expansion of the intellect through the

study of nature and science, and the application of reason to the experiences of

life.

. . .

you were led in the second degree, to contemplate the intellectual faculty, and

to trace its development through the paths of heavenly science . . . [line 27]

To

your mind, thus modelled by virtue and science, nature, however, presents one

great and useful lesson more—she prepares you, by contemplation, for the

closing hour of your existence . . . [line 32]

Truth

5.

That the active pursuit of reason and the expansion of the intellectual faculty,

subject to the will of God, will lead ultimately to truth and virtue, that is, a

totally fulfilled life.

Such,

my brother, is the peculiar object of the third degree in Freemasonry. It

invites you to reflect on this awful subject, and teaches you to feel that to

the just and virtuous man death has no terrors equal to the stain of falsehood

and dishonour. Of this great truth the annals of Freemasonry afford a glorious

example in the unshaken fidelity and noble d—— of our GM HA . . .

[line 39]

Hence

we see that, while human mortality and universal charity are emphasised,

Freemasonry considers self-development largely in terms of the expansion of

reason and the human intellect. Freemasonry is part of a long historical

tradition which defines personal development in terms of the intellectual

faculty.

Past

influences

Thinkers

and writers up to the nineteenth century, with their emphasis on reason and the

intellect, the development of rational systems, and the importance of experience

and observation, can be seen to have had considerable influence upon the Masonic

view of self-development. This paper shall briefly outline these three

influences.

Reason

and the Intellect

Reason,

knowledge and the intellect, since at least the time of the ancient Greeks, have

been recognised as central to an understanding of life and the universe.

Plato

(c.427–c.347 bce, The Republic)

saw the soul as being divided into three parts; the rational part or intellect,

the will, and the appetite or desire. He saw the ideal society, like the soul,

also being partitioned into three sections or classes, the philosopher kings,

the guardians, and the ordinary citizens. The philosopher kings were to lead the

people, for by reason and thought they came closest to an understanding of truth

and ultimate reality—what he called ‘ideas’ or ‘forms’.

Aristotle

(384–322 bce, Metaphysics)

did not speak of a separate world of ‘forms’ or ‘ideas’. He maintained

that the world of the senses, or the material world, is the real one. Aristotle

sought to find, by reason, cause-and-effect relationships between things in the

world.

The

early Christian writers tried to interpret Christianity and to relate it to the

philosophy of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

St Augustine

(345–430, The City of God) taught that all history is purposeful or directed

by God. He is above everything, and human beings and the world are God’s

creation. The supreme goal of human beings is a mystical union with God.

St Thomas

Aquinas (1265, Summa Theologica), who was influenced by Aristotle, took religious

philosophy a step further. He argued that the universe was organised on the

basis of reason, and that a knowledge of it leads to God. He said that a person

should use both faith and reason in believing in God.

The

views of these early philosophers, concerning the importance of reason, and the

intellect, for understanding the universe and for drawing close to God, are

echoed in the words of the Retrospect:

. . .

you were led in the second degree, to contemplate the intellectual faculty, and

to trace its development through the paths of heavenly science, even to the

throne of God. The secrets of nature and the principles of intellectual truth

were then unveiled to your view. [line 23]

Freemasonry

does not see a conflict between scientific endeavour and a belief in God. It

views knowledge about the universe as leading to a better understanding of the

creative laws of TGAOTU. As a consequence, Freemasonry emphasises the importance

of the intellect and reason in coming to understand the universe and the place

of human beings in it.

Rational

Systems

By

the use of their intellect, human beings have been slowly able, through

observation and reason, to develop an understanding of the physical, emotional

and spiritual environments, or systems, in which we operate.

A

system is a mental image which assists us to understand a more complex reality;

for example, a river system, a legal system, or a number system. It helps us to

obtain an overview of the whole situation, and to understand the important

variables that affect the object being studied.

It

was during the period of the European Renaissance (1400–1600), that scientists

used observation and reason to investigate the physical characteristics of the

earth and to develop the concept of a solar system. Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo

and Johannes Kepler saw themselves as discovering physical truths through

reason. They laid the foundation of measurement, experiment and mathematics upon

which Sir Isaac Newton (1687, Principia

Mathematica) built his great system of the world. Newton, in fact, described

the world as a giant machine, or system.

The

systems view of understanding is clearly evident in Masonic teaching, as seen

from the answer given by the second degree candidate to the question, What is Freemasonry? ‘A

peculiar system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols’ (Degree

Ritual, UGLV 1991, p 51).

The

systems view is also evident from the Retrospect:

But

it is first my duty to call your attention to a retrospect of those degrees

through which you have already passed, that you may the better be enabled to

distinguish and appreciate the connection of our whole system, and the relative

dependence of its several parts. [line 5]

Experience

and Observation

During

the 1700s, influenced by Newton’s work, philosophers adopted a practical

approach, and believed that experience and observation gave rise to knowledge.

For example, John Locke (1690, Essay

Concerning Human Understanding), spoke of the mind as a blank tablet upon

which experience writes. Experience acts on the mind through sensation and

reflections and these two processes give human beings their ideas and

understandings. David Hume (1739–1740, A

Treatise of Human Nature) also argued that all our knowledge is limited to

what we experience; that the only things we can know are objects and events of

sense perception and experience.

Masonic

teaching emphasises the importance of experience and observation, not just

visual observation but also mental observation or contemplation. From the Retrospect

we see the importance of experience and the contemplation of that experience for

gaining an understanding of ourselves, life and death.

To

your mind, thus modelled by virtue and science, nature, however presents one

great and useful lesson more—she prepares you, by contemplation, for the

closing hour of your existence, and when, by means of that contemplation, she

has conducted you through the intricate windings of this mortal life, she

finally instructs you how to die. Such, my brother, is the peculiar object of

the third degree in Freemasonry. [line 32]

The

Masonic view of self-development has been influenced by past philosophers, and

particularly by the development of scientific method following the European

Renaissance. Freemasonry understands self-development in terms of an increase in

knowledge, acquired by observation, reasoning, experiment, measurement and the

construction of mental systems, to assist an understanding of the world and the

meaning of human life.

As

a system of rational personal development, Freemasonry has an important role to

play, both now and in the future—although the world of the mid-21st century

will be substantially different from that of today.

Societal

trends

The

wonderful thing about the future is that it can be guessed at. The future is not

known, for the universe and human life are full of paradox and surprise (Adams,

1992). Nevertheless, tomorrow is connected to yesterday via today, and we can

discern trends that are likely to become major characteristics of future society

which will substantially affect individual self-development. These trends

include an increase in personal freedom, an increase in scientific discovery,

and an increase in the rate of social change.

This

paper shall briefly consider these trends and their implication for personal

development and the role of Freemasonry.

Increasing

personal freedom

Since

the mid 1700s there has been an expansion of theory and practice supporting

increased individual freedom, particularly in the areas of the economy,

government and society. For example, there has been the development of national

economic systems based largely on the theory of competitive markets, in which

individual freedom to make production and distribution decisions is paramount.

In

government, the fundamental individual liberties of expression, religion,

assembly and equity have been enshrined in Bills of Rights, constitutions and

laws. In society there has been the development of a philosophical perspective

(sometimes called existentialism) which encourages social and behavioural

experimentation, human life being seen basically as a series of decisions that

must be made with no way of knowing conclusively what the correct choices are.

In

a world of increasing personal options, individuals will have greater freedom to

make their own choices. But they will also be increasingly made accountable for

their choices.

Increasing

scientific discovery

Many

areas of science and intellectual endeavour are making important contributions

to our understanding of the world and self-development. For example: in

chemistry, with the development of polymers, synthetic fibres, compounds and

pharmaceutical drugs; in microelectronics, with the development of the

micro-chip, the computer, the visual display unit and communication networks; in

medicine, with the development of ultra-sound diagnosis, fibre optics and laser

beam surgery, organ replacement and repair operations; in genetics, with the

manipulation and evolution of the DNA code of animals, vegetables, and bacteria;

and in astronomy, with the use of satellites to help discover the history of the

universe.

The

pace of scientific discovery is increasing over time and the effects are having

a profound impact on the way in which we understand and interpret the world, and

experience life.

Rapid

social change

The

effect of increasing personal freedom and increasing scientific discovery is

that the individual in the twenty-first century will face a world characterised

by an increasing rate of change. Such change can be enormously beneficial, but

the difficulty for the individual is one of adjusting to an increasingly

transient world. What Alvin Toffler (1972) called ‘future shock’ will be

suffered by many people. The failure to effectively adapt to social change can

result in the individual suffering a sense of insecurity, disorientation,

alienation, and ultimately a lack of meaning of self and of life in general.

Role

for Freemasonry

In

June 1992 the Weekend Australian

produced a series of articles under the general heading of ‘Creating the

Future’. This series brought together the views of nearly one hundred of

Australia’s leading thinkers. In a summary article at the end of the series,

the newspaper columnist Philip Adams made the point that our personal freedom,

technologies, pace of human life and inventions are out-distancing our

philosophies, ethics and laws. He observed that in every area of science we need

to be better informed, but we must remember that data is not information,

information is not knowledge and knowledge is not wisdom. He wrote: ‘There’s

an awful lot of data around, and information in unprecedented amounts. But

wisdom? That’s in short supply. Indeed it may be becoming rarer, more

elusive’. (Adams, 1992, p 18)

Here

then, is a major role for Freemasonry in this age of individualism, materialism,

free choice and transience: to provide a moral basis for wise decision-making

and self-development. Freemasonry, through its well-defined and stable authority

structures, rituals and illuminating allegories, provides an environment of

peace and harmony in which the intellectual faculty is encouraged to develop and

in which moral values and wisdom are fostered in the individual.

Freemasonry

emphasises that self-development depends upon the individual’s improved

knowledge and understanding of himself and the world about him. Freemasonry

reminds us that self-development is undertaken in a material world, and that the

development of the intellectual faculty occurs within a mortal body. It uses the

tools of operative masons and translates their use into moral values and the

building of the spirit. It leads the individual ultimately to recognise that

reverence and respect for God is wisdom, and that to shun evil is understanding

(Job 28:28).

Although

Freemasonry is veiled by the mist of the past, it points to God and eternity. It

is concerned with the past, the present and the future, and belongs to future

ages. (Wiley Odell May, in Dewar, 1966, preface) Freemasonry has an important

role to play in providing responsible opportunities for individual

self-development, for its members and others, in a world which is increasingly

characterised by creative individualism, scientific discovery and pervasive

change.

Community

acceptance

There

remains an unanswered question. If Freemasonry has an important role to play in

providing responsible opportunities for self-development for its members and

others in the twenty-first century, why is this not generally acknowledged by

the community? It could be because Freemasonry lacks an adequate understanding

of itself, and because it lacks an outlook recognised by the community as

relevant to the twenty-first century.

Prior

to undertaking the second degree ceremony, the candidate is asked, ‘What is

Freemasonry?’ and the required response is, ‘A peculiar system of morality,

veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols’. (Degree

Ritual, UGLV 1991, p 51). But this is only a partial truth. Freemasonry

is not simply a peculiar system of morality veiled in allegory and illustrated

by symbols. First and foremost it is a way of understanding the universe in

which we live and how we relate to it and to one another.

Before

you can have a morality or morality system, you must have understanding, a

conceptual view of the world and humans within it. Understanding precedes

morality. Morality is simply acceptable motivation and behaviour, based on a

given understanding of the world. There is the need for a new approach, a

conceptual analysis of Freemasonry.

A

Conceptual Model

The

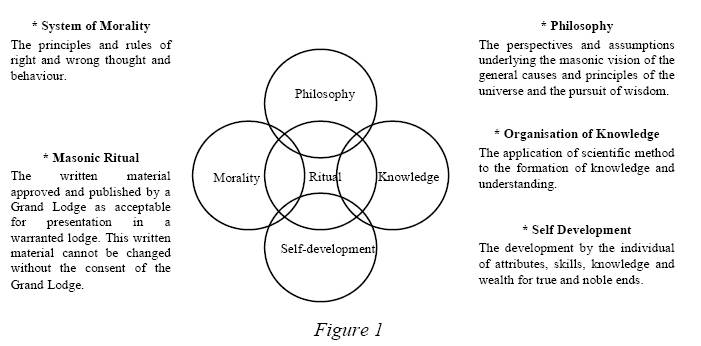

explanation of the Masonic approach to self-development presented in this paper

suggests the following conceptual model (Figure

1) of interrelated components.

This

paper in fact provides and initial exploration of the ritual, philosophy and

self-development components of this model of Freemasonry. The paper also implies

that the significance of the model components may vary over time. That is, the

model is not static.

A

Dynamic Analysis

The

important role that Freemasonry can play in the twenty-first century is not

generally acknowledged, because the community does not see Freemasonry as

relevant. Aspects of morality and charity have been effectively passed from one

generation of Craft brethren to the next via Masonic ritual. However, there has

been a failure to adequately spell out the philosophy, the outlook and

assumptions, underpinning Freemasonry, and a failure of the Masonic approach to

adequately respond to changing individual and community values. Figure

2 provides a diagrammatic representation of the problem.

Need

For Relevance

A

brief outline of the development of western values and perspectives since 1600

will illustrate how Freemasonry has failed to remain relevant in an ever

changing world.

Recent

historical research indicates that Freemasonry was very much influenced by the

English and French Enlightenment which began in the 1600s and lasted till the

late 1700s. The Enlightenment was characterised by the view that knowledge and

society is not advanced by habit or superstition, but by reason, that is, by

logic and the rational scientific approach to understanding. The Enlightenment

saw the continuing separation of the State from the Church, with men and women

increasingly putting their fate in their own hands rather than in that of God or

the Church.

The

Enlightenment was also characterised by the notion that the law should be based

on natural and equal rights for all. That is, the right of education, freedom of

speech and religion. The period of the Enlightenment was accompanied by the rise

of British middle-class respectability and semi-religious activities, and the

establishment of gentlemen’s studies, libraries, galleries, clubs,

societies—and Freemasonry.

The

views of the Enlightenment generated the assumptions and perspectives which

underlie Freemasonry of the 1700s and 1800s. These Masonic perspectives and

assumptions included:

*

a belief in a single Supreme Being

*

the presence of an all-seeing eye and an invisible hand to oversee human

activities

*

a view that God created the world so that it could be understood by the

reasoning power of humans; and that the laws of nature can be discovered by

mathematics—in particular, geometry

an

understanding that human nature and conduct is well ordered and, like the

physical universe, a science of human nature and society is possible

*

that there is a link between scientific reasoning, understanding and the

discovery of truth

*

an acknowledgment of the importance of education, for it teaches good methods of

reasoning

*

the promotion of the value of labour, the work ethic, the protection of trade

skills

*and

the acceptability of secrecy in organisations to control membership and

standards.

These

assumptions and perspectives still underlie much Masonic ritual and practice.

However, the philosophy, perspectives and assumptions underlying current

Freemasonry are substantially different from the prevailing values, attitudes

and understandings in the community today. For example, prominent community

perceptions include:

*

the separation of religion from everyday life

*

a quest to find sustainability rather than God

*

an awareness of the conflict of objectives.

The

invisible hand is not seen to operate, and what is good for the individual is

not necessarily good for society: for example, the need to reconcile individual

liberty on the one hand, with equality on the other.

There

is also the demand for confirmed historical accuracy, with a general ignorance

of the Bible, particularly the Old Testament. There is an acceptance of the link

between education, scientific reasoning and understanding, but not necessarily

between education and the discovery of truth. It is acknowledged that there are

few rational truths or absolutes. Statements about the world or human behaviour

are never certain, they are only probable at best, and value systems are based

largely upon situational ethics. There is the declining importance of skilled

physical labour and trade labour, and the increasing requirement for

organisational accountability and transparency.

Research

directions

The

conceptual model (Figures 1 and 2), by highlighting the key attributes of Freemasonry,

not only focuses attention on philosophical aspects of the Craft, but also

provides coherent direction for future Masonic research:

(1)

more specific and precise definition of the model components: for example, a

more complete understanding of current theories of knowledge formation and

learning.

(2)

more complete analysis of the key relationships between the model components:

for example, the link between philosophy (such as Buddhism) and Masonic ritual.

(3)

the measurement and quantification of the model components and the direction and

strength of the key relationships between the components: for example, the

relationship of morality (such as beneficence) to self-development.

(4)

the change in the model components and relationships over time: for example, the

impact of World War Two veterans upon the development of Freemasonry.

(5)

the application of the conceptual model to the analysis of organisational

performance: for example, the divergent roles and functions of Grand Lodge and

warranted lodges.

Conclusion

There

is no doubt that Freemasonry has a great deal to offer in terms of wise

decision-making in an increasingly transient world. Whether Freemasonry will

make a substantial positive contribution to future society will ultimately

depend upon reconciling the disparity between the philosophy, the perspectives

and assumptions of Freemasonry, and current community perceptions and values.

The

way forward is not to double our efforts on ritual, or to increase our

benevolence, or even to strive for new members. These will necessarily follow if

we rediscover the Masonic vision of the ritual-writers. To go forward we must

first understand the philosophy upon which our ritual is based. Then we must

reinterpret that philosophy in the light of a changed world.

For

example, it is about developing a meaningful understanding of God for all

monotheistic believers. It is about uniting these believers into a caring,

peaceful and harmonious brotherhood, which transcends religious, cultural,

national, ethnic and locational boundaries and barriers. It is not about secrecy

and exclusion. It is about world community, expansive inclusion, transparency

and accountability.

It

is not simply about benevolence shown to those in distress, the aged, the sick,

the poor, and disaster victims. It is equally about the moral development of the

young, through the removal of discrimination and vilification and through such

activities as drug-free sport and recreation. It is about the development of the

skill and intellectual levels of all humans to ensure sustainable families,

friendships, communities, and material lifestyles.

It

is about moral regeneration, in all aspects of life. And it begins with the

individual, the young and the family. We failed to capitalise on the large

Masonic memberships of the 1950s and 1960s because of excess secrecy, habit and

protocol. In effect, we locked our families out of Freemasonry.

The

Masonic vision is about providing its members with a moral basis for

decision-making. It is about values and standards based on a VSL, not upon

professional association standards and situational ethics. To catch the Masonic

vision requires a return to the underlying principles and tenets, the

philosophy, upon which Freemasonry is founded. And having understood that

philosophy, to interpret and apply it to a radically changed world.

References

Adams,

P: ‘Choosing the Right Direction for Change’ in the Weekend

Australian, 27/28 June 1992, p 18.

Beagley,

D: ‘Enlightened Histories of Our Times’ in Freemasonry

Victoria, Issue 83 February 2000, pp 14–15.

Brewer,

J: The Pleasures Of The Imagination:

English Culture in the 18th Century, Harper Collins.

Dewar,

J: The Unlocked Secret: Freemasonry Examined, William Kimber & Co, London

1966.

Holy

Bible

(1994) New International Version, Zondervan.

Rees,

J: ‘Spirituality in Freemasonry’, Canonbury Masonic Research Centre, London

March 2000, <http//www.canonbury.ac.uk/closed/lectures/julian.htm>.

Roche,

D: France in The Enlightenment, trans

A Goldhammer, Harvard University Press.

Toffler,

A: Future Shock, Pan Books 1972.

United

Grand Lodge of Victoria: Degree Ritual (1st 2nd & 3rd Degrees) 1991.

———

Information for Fellow Crafts.

World

Book Encyclopedia

(1982) vol 1, pp 129–130; vol 15 pp 345–352.

APPENDIX

A

THE

AIM OF FREEMASONRY IS TO:

*

Practice universal charity

*

Provide opportunities for self development

*

Build friendships

*

Foster moral standards

*

Seek excellence in all pursuits

(Degree

Ritual, UGLV, 1991, p 1)

APPENDIX

B

Retrospect

|

Line

Ref

|

|

|

[1]

[5]

[11]

[15]

[20]

[27]

[32]

[39]

[49]

|

Bro —, having taken the great and solemn

obligation of a MM, you have now a

right to

demand of me that last and greatest trial, by which

alone you can be admitted

to a participation in the

mysterious s . . . ts of a MM. But

it is first my

duty to call your attention to a retrospect of those

degrees through which

you have already passed,

that you may the better be enabled to distinguish

and appreciate the connection of our whole system,

and the relative dependence of its several parts.

Your admission into Freemasonry in

a state of

helpless indigence was an emblematical represen-

tation of the entrance of all men on this, their

mortal existence. It inculcated the useful lessons

of natural equality and mutual dependence, it

instructed you in the active principles of universal

beneficence and charity, to seek the solace of your

own distress by extending relief and consolation to

your fellow-creatures in

the hour of their affliction;

above

all, it taught you to bend with humility and

resignation to the will of

the GAOTU, and to

dedicate your heart, thus purified from every bane-

ful and malignant passion, fitted only for the

reception of truth and virtue, as well to His glory

as the welfare of your fellow-creatures. Proceeding

onward, still guiding

your steps by the principles

of moral truth, you were led in

the second degree,

to contemplate the intellectual faculty, and to trace

its development through the paths of heavenly

science, even to the throne of God. The secrets of

nature and the principles

of intellectual truth were

then unveiled to your view. To

your mind, thus

modelled by virtue and science, nature, however,

presents one

great and useful lesson more – she

prepares you, by contemplation, for the

closing hour

of your existence, and when, by means of that

contemplation, she has

conducted you through the

intricate windings of this mortal life, she finally

instructs you how to die. Such, my

brother, is the

peculiar object of the third degree in Freemasonry.

It invites you to reflect on this awful subject, and

teaches you to feel that

to the just and virtuous

man death has no terrors equal to the stain of

falsehood and dishonour. Of this great truth the

annals of Freemasonry afford a glorious example

in the unshaken fidelity and nobled . . . of our

GM HA, who was s . . . just before the completion

of KST, at the construction of which he was, as

you are doubtless aware, the principal architect.

|

(Degree

Ritual, UGLV, 1991, pp 92–94)

| ![]() News Feed |

News Feed |  Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email